Authors: Maciej Eder, Jan Rybicki

Category: Paper:Long Paper

Keywords: authorship attribution, Harper Lee, Truman Capote, mixed authorship

Go Set A Watchman while we Kill the Mockingbird in Cold Blood, with Cats and Other People

Even before Harper Lee’s “new” book, Go Set A Watchman, was published earlier this year (2015), rumors as to its authorship abounded. Alabama police looked into alleged abuse of Lee’s rights; suspicion suddenly (re)surfaced about the strange fact that one of the greatest bestsellers in American history was its author’s only completed work; Lee’s childhood friendship with Truman Capote (portrayed as Dill in To Kill A Mockingbird) and their later association on the occasion of In Cold Blood fueled more speculations on the two Southern writers’ possible, or even just plausible, collaboration; finally, the role of Tay Hohoff, Lee’s editor on her bestseller, was discussed. Desperate media turned to the usual front for stylometry, Matt Jockers, who graciously ceded this opportunity onto us. A story about our early results appeared in The Wall Street Journal (Gamerman, 2015), and it echoed even in our native Poland, where the country’s major newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza, also devoted a whole page to this international success of Polish stylometry (Makarenko, 2015).

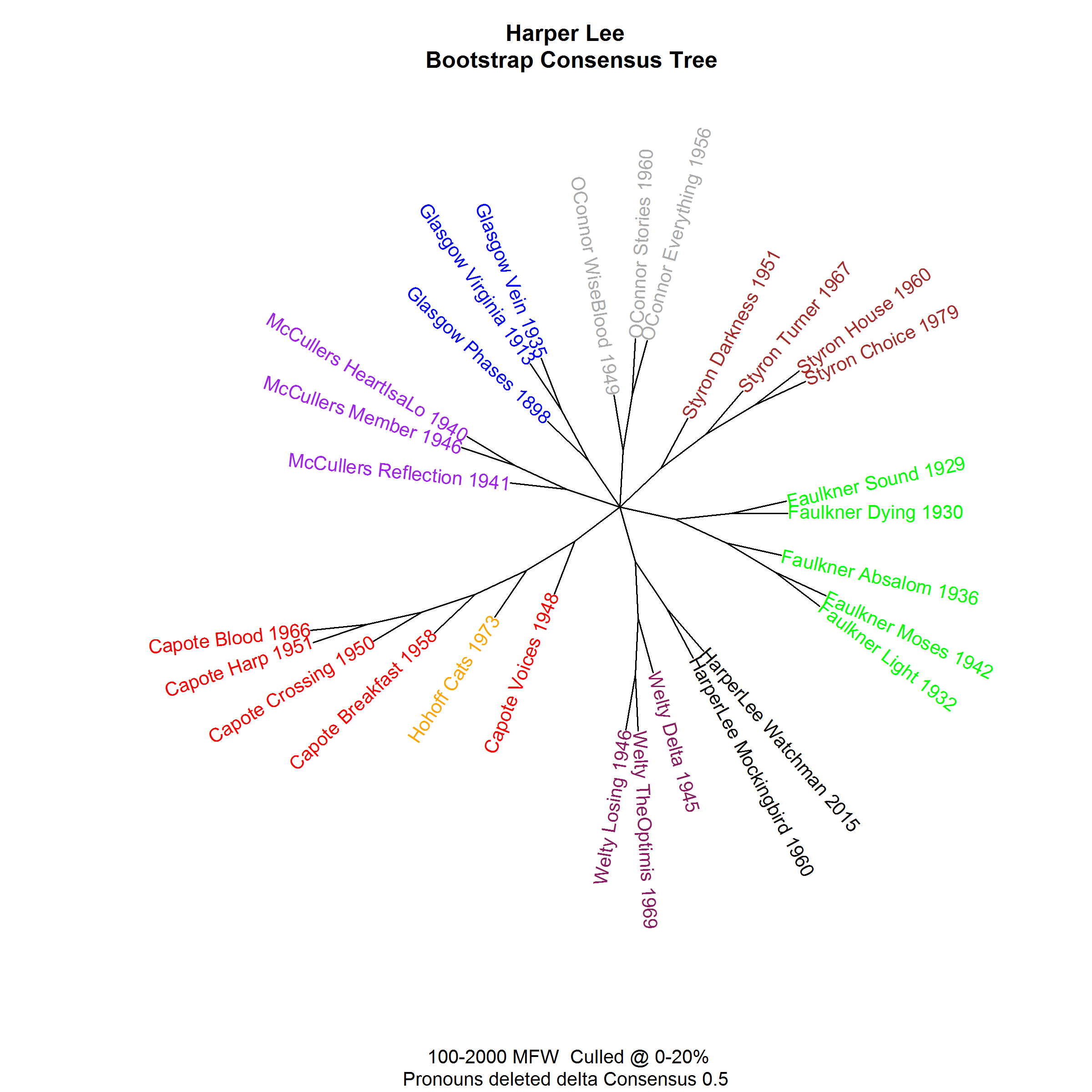

The truth proved to be at once much less sensational than most of the rumors – and much more interesting. Stylometric evidence is very strong in this case: Harper Lee is the author of both To Kill A Mockingbird and Go Set A Watchman. The first method applied here was part of stylo, a stylometric package (Eder et al., 2013) for R (R Core Team, 2014): series of most-frequent word frequencies in a collection of texts were compared using Burrows’s Delta measure of distance (Burrows, 2002); Delta distances were compared for each pair of the texts in this corpus by cluster analysis, and the results of clustering were used to create a bootstrap consensus tree. The resulting Fig. 1 shows the two Harper Lee books as two nearest neighbors just as it does the other authors included for comparison here. More importantly, perhaps, Truman Capote is far away. Most importantly, her editor’s only available book, Cats and Other People, betrays no similarity to her charge. Since this sort of diagram is oriented at deciphering the strongest signal in word usage, authorship, the various rumors should be finally set at rest – the more so as the two Harper Lee novels have always been each other’s nearest neighbors in a whole series of rigorous machine-learning classification tests performed using stylo’s “classify” function.

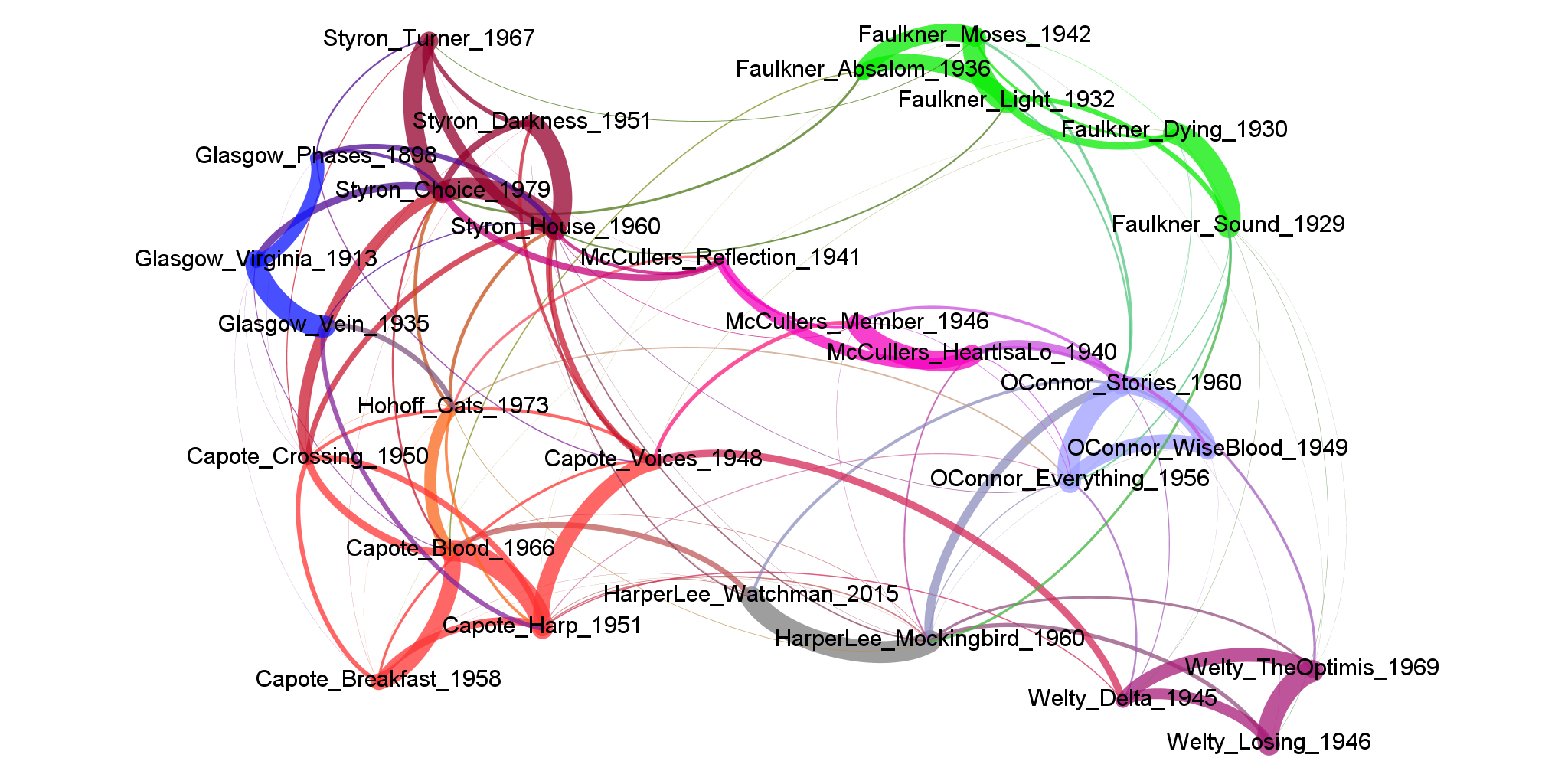

Lesser affinities between texts are preserved in Fig. 2, which presents a network analysis of the same data treated with an enhanced version of the aforementioned consensus statistical method (Eder, 2015b) and produced with the Force Atlas 2 layout (Jacomy et al., 2014) in Gephi (Bastian et al., 2009). The degree of similarity is shown by the thickness of the curves that connect the particular texts: the thicker the line, the stronger the similarity. Additionally, the algorithm also spatially distributes the nodes (representing each text) to provide an additional visualization effect.

It is no surprise that this diagram echoes the previous one as far as the strongest similarities are concerned. Lee is still Lee; now, Faulkner stands almost alone. But then the lesser forces, represented by the slightly narrower connections, also count. The first thing that strikes the eye in the Lee neighborhood is the Watchman’s affinity to In Cold Blood and a more heterogeneous pattern for the Mockingbird: the book researched by Capote with Lee is still linked to her 1960 bestseller, but now only by the minutest of lines. This rephrases the Lee/Capote question in a more interesting way. Is there a drop of Capote in Lee? Perhaps not in the entirety of her work – perhaps just in a passage or two. This should be answered with a modification of the method: since it is difficult to see overlapping stylometric signals in an entire novel, one can see much more when the novel is split into equal and smaller fragments; then, the usual stylometric analysis is applied to the particular slices according to the “rolling.classify” procedure (Eder, 2015a).

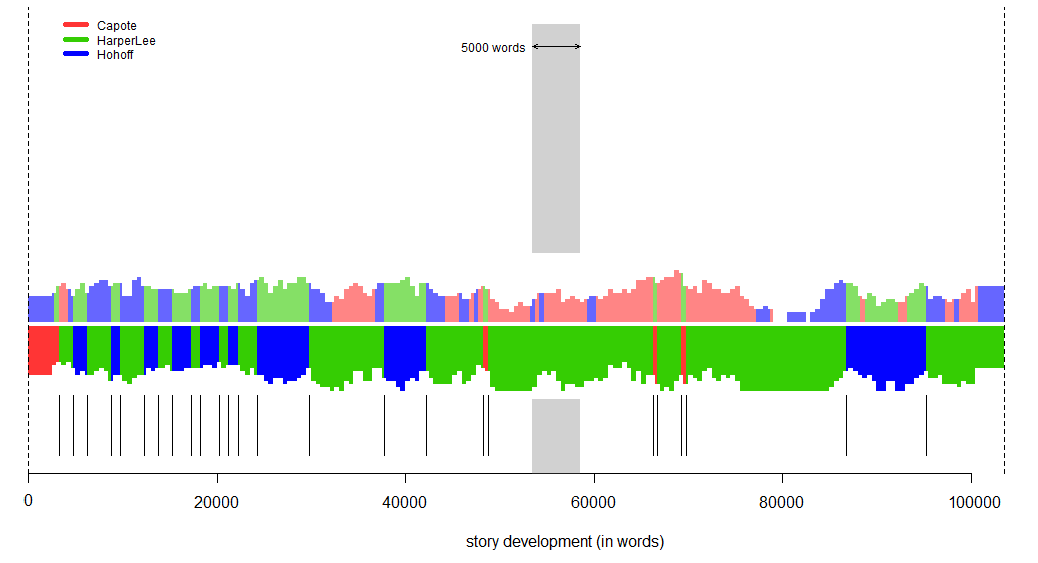

The most reasonable texts to be thus compared to To Kill A Mockingbird are Capote’s In Cold Blood (since Lee helped with the research for that book), Lee’s own Go Set A Watchman (to see how much of the Watchman might be found in the Mockingbird) and Tay Hohoff’s Cats and Other People (to find out how much of Lee’s rewriting of her original proposal might have been influenced by her experienced editor). This is presented in Fig. 3, and the result is quite interesting.

The signal in a little more than a half of the segments in To Kill A Mockingbird is that of the novel she originally brought to be published by Lippincott. It is highly significant that its longest stretch coincides with the trial that was only mentioned in the Watchman and became the focus of the book in the Mockingbird. This seems to suggest that while this refocusing of the book was made following the advice of the editor, the rewriting was indeed done by Harper Lee.

The rest of the Mockingbird is a veritable mosaic of her own and her editor’s hand. Tay Hohoff’s impact seems to be especially visible towards the end of the story, and it coincides with the novel’s climax in Chapter 28: Scout, dressed in her elaborate and cumbersome ham costume, is attacked by Bob Ewell, who, following the struggle with Jem and then with Arthur “Boo” Radley, is left with his own knife stuck under his ribs.

We will never know, of course, whether Tay Hohoff really wrote that scene (and the others that seem to bear her mark) for Lee. But it is sensible to argue that while To Kill A Mockingbird is obviously a novel by Harper Lee, traces of someone who helped her along the way for two whole years – and who, at one point, talked the author into running down to the street to collect the manuscript that had been flung through the window in frustration (Shields, 2006: 121) – must be there somewhere. The results produced by the different functions of stylo are not in conflict when they show the overall strength of the Watchman signal in the Mockingbird and the possible echoes of Hohoff (or even, at the very onset of the novel, of Capote) in selected segments. Rather, they seem to provide new insights into the traces of various people involved in the making of a novel – and into how some of these traces may be identified and discerned by stylometry. It is equally sensible to find such traces in a work of a very particular kind: a novel that has been reprocessed almost beyond recognition in a long process of authorial and editorial collaboration; where the final version keeps the setting and the characters of the first, but changes its focus, its historical moment in time and, perhaps more importantly, its ideological message.

- Bastian M., Heymann S., Jacomy M. (2009). Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.

- Burrows, J. (2002). “Delta”: A measure of stylistic difference and a guide to likely authorship. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 17: 267–87.

- Eder, M. (2015a). Rolling stylometry. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 30, first published online: 7 April 2015, doi: 10.1093/llc/gqv010.

- Eder, M. (2015b). Visualization in stylometry: cluster analysis using networks. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 30, first published online 3 December 2015, doi: 10.1093/llc/fqv061.

- Eder, M., Kestemont, M. and Rybicki, J. (2016). Stylometry with R: a package for computational text analysis. R Journal, 8, first published online 30 December 2015, https://journal.r-project.org/archive/.

- Gamerman, E. (2015). Data Miners Dig Into “Watchman”. The Wall Street Journal, 17 July 2015: D5, http://www.wsj.com/articles/data-miners-dig-into-go-set-a-watchman-1437096631.

- Jacomy, M., Venturini, T., Heymann, S. and Bastian, M. (2014). ForceAtlas2, a continuous graph layout algorithm for handy network visualization designed for the Gephi software. PLoS ONE, 9(6): e98679, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098679.

- Makarenko, V. (2015). Literackie śledztwa Polaków. Gazeta Wyborcza, 31 July 2015: 18.

- R Core Team (2014). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Wien, http://www.R-project.org/.

- Shields, C. J. (2006). Mockingbird: A Portrait of Harper Lee. New York: Henry Holt and Co.