Authors: Anastasia Bonch-Osmolovskaya, Elena Sidorova, Daniil Skorinkin

Category: Paper:Poster

Keywords: literary studies, narrative, POV structure, machine learning

Verbal Identity of a Fictional Character: a Quantitative Study with a Machine Learning Experiment

1. Introduction

The idea that narrative literature comprises two distinct types of speech – that of the narrator and that of characters – dates as far back as Plato’s Republic. The philosopher distinguished diegesis (narrative, narration), when the author speaks for himself, from mimesis (imitation, enactment), when the author puts words in the mouths of his or her fictional actors.

Modern narratology places high emphasis on the concepts of point of view (POV) and POV structure of a text (Schmid, 2003), which are often expressed through specific combinations of author’s and character’s speech. Authors may switch between the POV’s by employing character-specific lexica and the use of temporal and spatial references that indicate certain POV (Uspensky, 1983).

Leo Tolstoy was one of the writers known for conscious usage of such means to differentiate between the character POV’s. He was a firm proponent of the idea that each character has to speak his/her own language if the book was to be convincing. Critics confirm that Tolstoy’s characters do have their personal styles of conversation.

In this paper we made an attempt to provide quantitative grounds for these claims. For that purpose we extracted all speech activity instances from War and Peace, attributed them to the speaker characters and used the data to train a classifier. Our hypothesis was that if Tolstoy’s characters actually possessed these unique speech features, the classifier would be able to predict the speaker with some tolerable accuracy.

2. Data

Instances of direct speech were extracted from the text with help of ABBYY Compreno (Starostin et al., 2014). For more details on the extraction procedure see (Bonch-Osmolovskaya A., Skorinkin D., 2015). The total number of extracted speech instances was 6853, of which 4476 had their speakers identified.

Apart from the speaker, a number of additional attributes were extracted for each instance: text of the speech, text of the author’s introduction (‘she cried’, ‘he said with a laugh’), normalized speech predicate (‘to say’, ‘to cry’, ‘to whisper’, ‘to burst out’), the number of question and exclamatory phrases within one speech, the number of words in the speech and the number of punctuation marks.

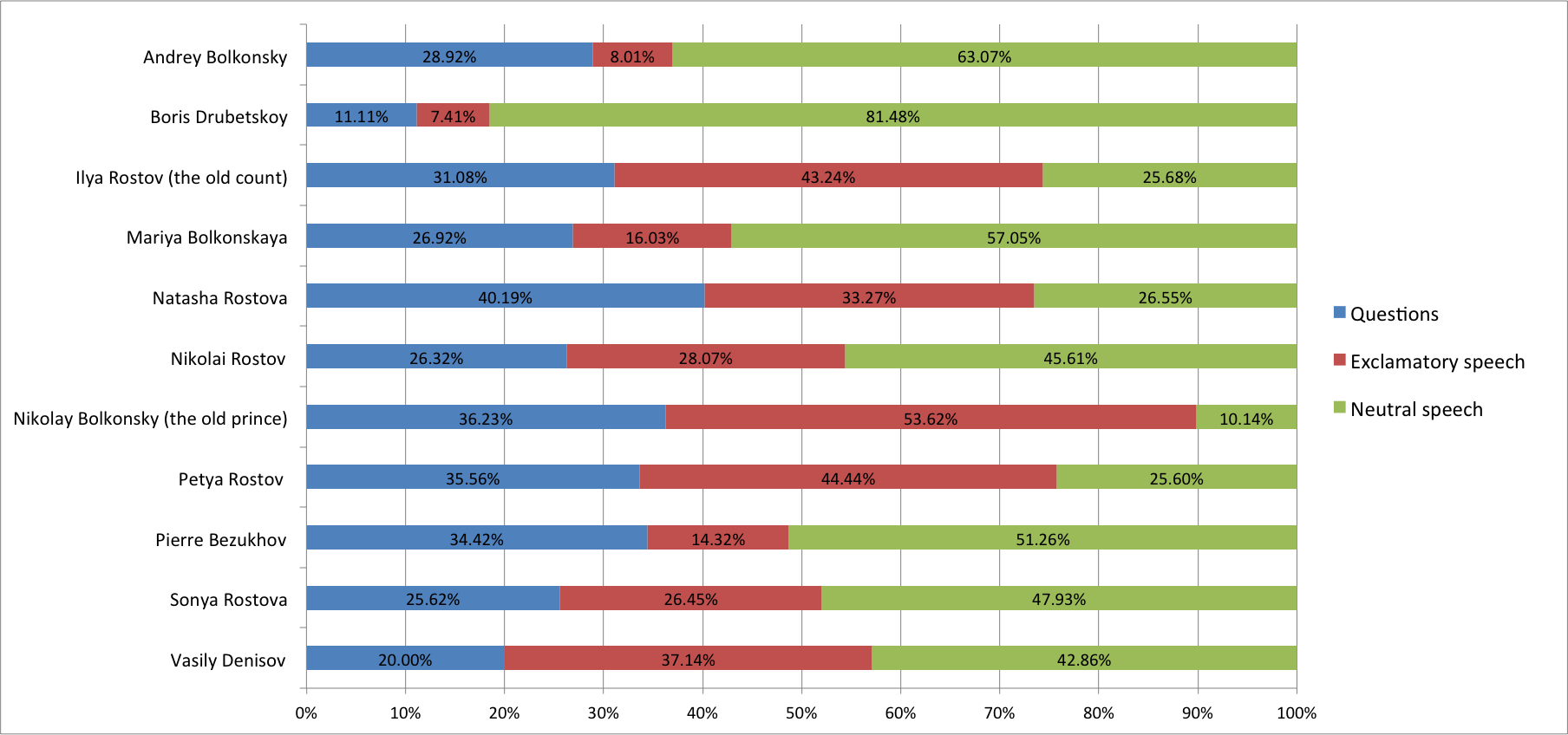

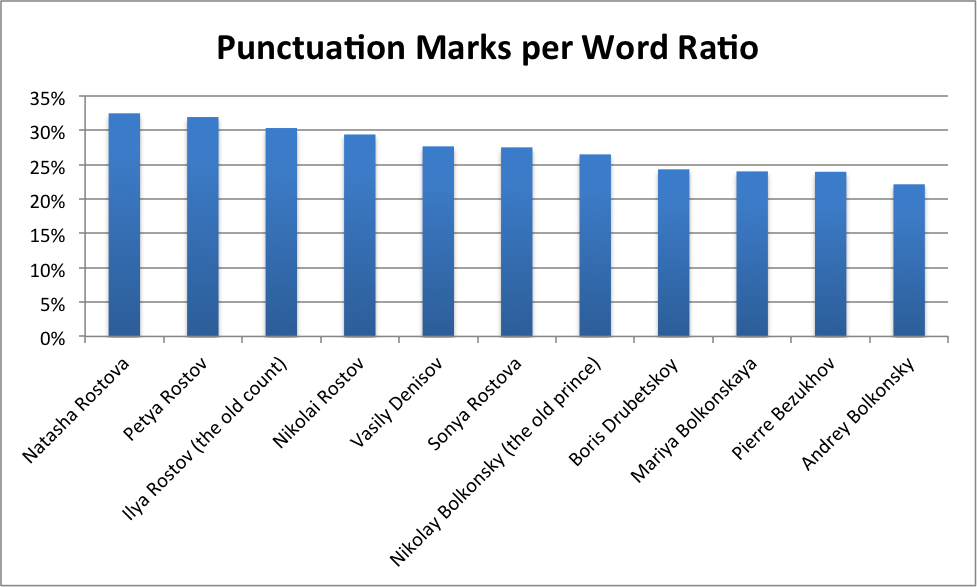

Before we carried out the experiment we attempted to analyze the data and detect potentially informative features. It appeared that certain characters (Natasha Rostov, Nikolai Rostov) tend to speak in short intermittent bursts and exclaim a lot, so they were expected to have higher average punctuation marks per word ratio and bigger shares of exclamatory speech. To confirm this intuition we gathered some aggregated statistics (see Fig. 1).

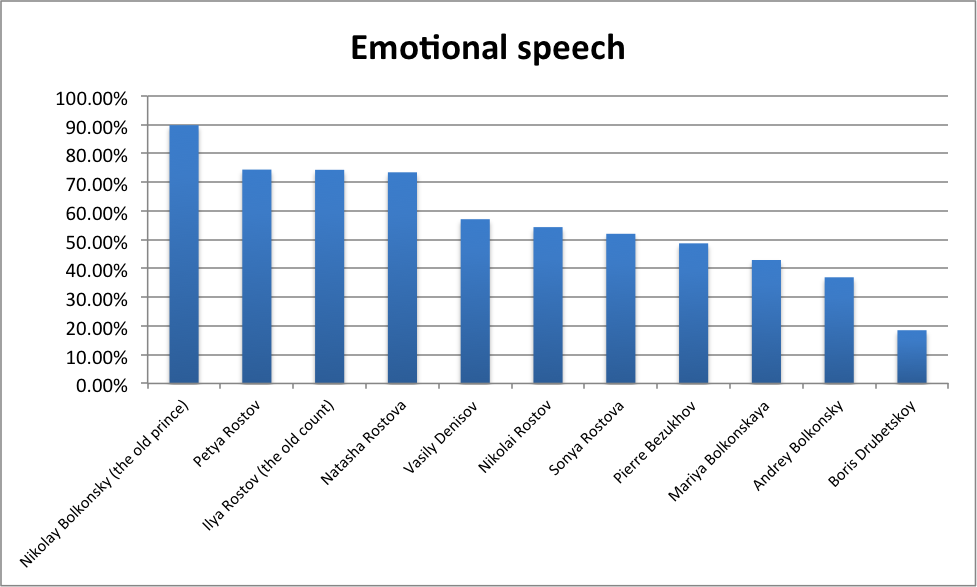

Exclamatory and question phrases together make up the ‘emotional part’ of a character’s speech. Its share (Fig. 2) seems to correlate with age extremities. Prince Nikolay Bolkonsky is probably the oldest of the main characters, and as his age gets the better of him in the course of the novel, he turns more and more emotional and impulsive; Petya Rostov, on the other hand, is an exuberant and emotional boy, the youngest of the Rostov family.

Fig. 3 reflects character’s overall punctuation marks per word ratios. Seems like the ‘burst speech’ pattern is hereditary within the Rostov family:

3. Machine learning experiment

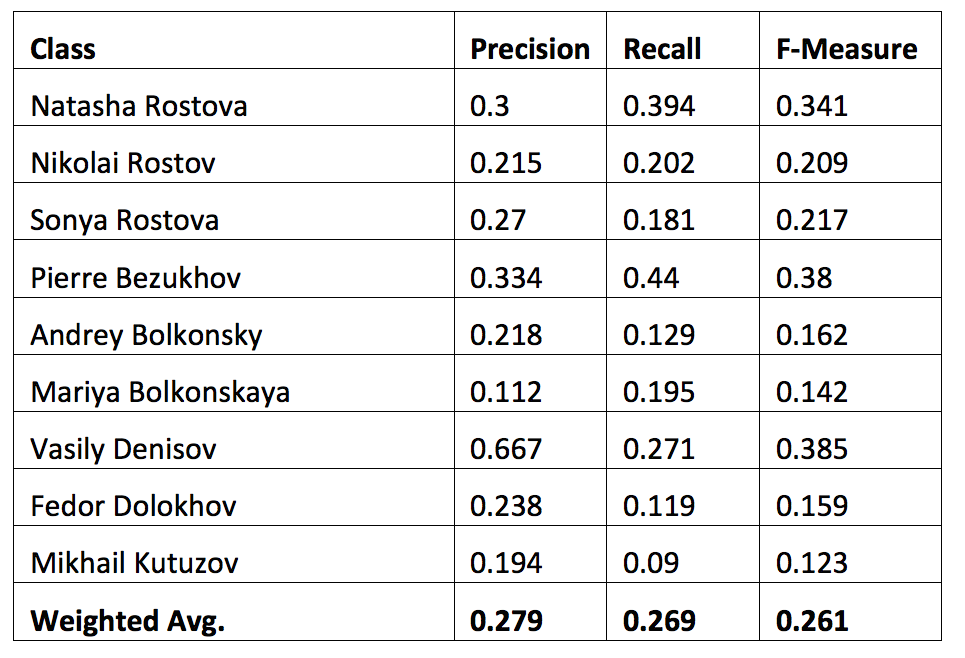

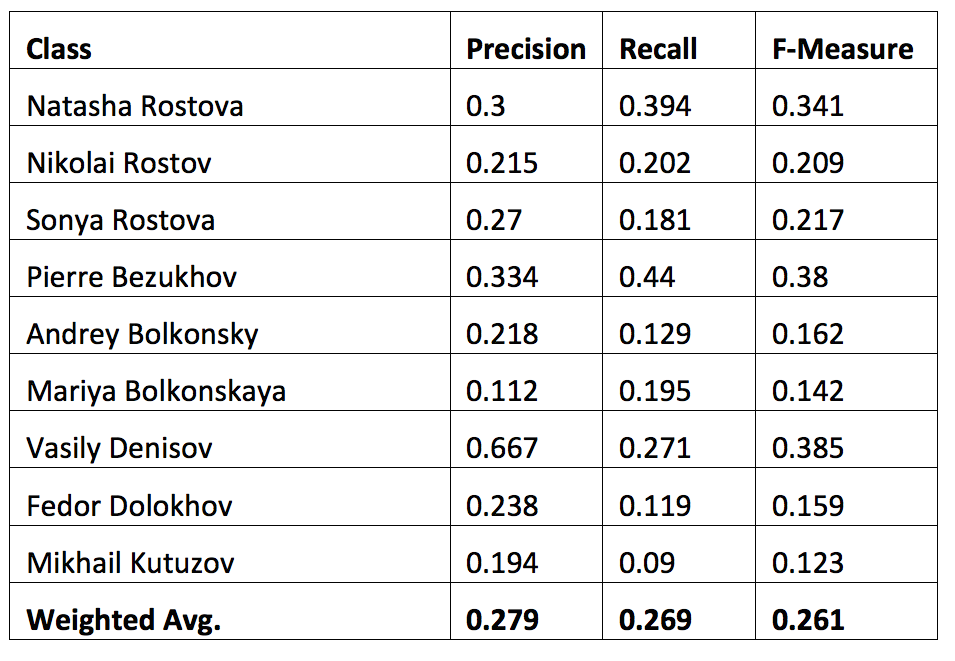

Next step was to try and use some of these features to train a classifier. We used several standard algorithms, of which Random Forest demonstrated the best results. At the first stage we created a baseline by training the classifier solely on the lemma and word form frequencies of speech. Table 1 shows the results we obtained.

The second stage was to add formal features that we considered informative (number of exclamatory phrases, number of questions and punctuation marks per word ratio) and retrain the classifier. The results we obtained show that the use of these features slightly improved performance.

4. Results & discussion

Our first attempts to automatically classify speaker in Tolstoy’s text did not prove successful. The best F-measure we were able to obtain so far does not exceed 0.385 for an individual character. However, we were able to show that some formal features, such as punctuation marks per word ratio or the number of exclamatory/question sentences, might improve classification quality. This assumption can be confirmed by the figures in the Data section, where the aggregated values of features correspond with certain character traits that are apparent to the human reader.

- Bonch-Osmolovskaya A., Skorinkin D. (2015). Automatic semantic tagging of Leo Tolstoy’s works. In Abstracts of Digital Humanities – 2015 conference, Sydney, Australia. http://dh2015.org/abstracts/xml/SKORINKIN_Daniil_Automatic_semantic_tagging_of_Le/SKORINKIN_Daniil_Automatic_semantic_tagging_of_Leo_Tols.html (accessed 06 March 2016)

- Eichenbaum, B. (2009). Works on Leo Tolstoy. Saint-Petersburg. SPBSU Faculty of Philology and Arts.

- Schmid, V. (2003). Narratology. Moscow: LRC Publishing House.

- Starostin A. , Smurov I., Stepanova M. (2014). A Production System for Information Extraction Based on Complete Syntactic-Semantic Analysis. Computational Linguistics and Intellectual Technologies: Proceedings of the International Conference ‘Dialogue’, Bekasovo, pp. 659–667.

- Uspensky, B. (1983). A Poetics of Composition: The Structure of the Artistic Text and Typology of a Compositional Form. Oakland: University of California Press.